Brett Olmsted has a Ph.D. in 20th century U.S. History with a focus on Latinx culture, labor, and immigration and is a Professor of History at San Jacinto College.

In late August 2022, I received a message from my daughter’s second grade teacher. It was time to buy class shirts.

This is normally a very cute thing for kids, having parents purchase a t-shirt so their children don’t feel left out (an item that will likely be worn only a few times before being too small). My daughter is in a Spanish Immersion Program, so, naturally, the shirt was expected to reflect this designation somehow.

However, the image that appeared on my phone was of a blue jay (the school mascot) with a sombrero on its head. This image drew an immediate reaction of “this is just not right.”

This tendency of putting a sombrero on something or someone to make it “Hispanic” or “Mexican” or “Latinx” is pervasive.

A quick online search reveals several recent and notorious examples of Anglos donning sombreros as a joke or to promote “Mexican” themed events.

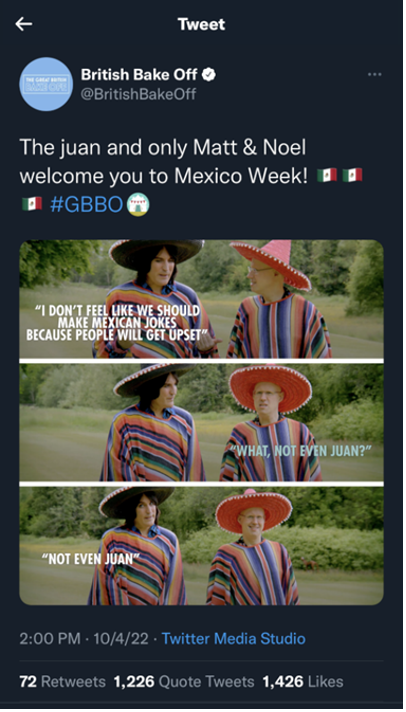

One such image appeared as a tweet from the Fall 2022 season of the television show The Great British Bake Off, as two Anglo hosts walk through a field wearing sombreros and serapes in their attempt to dress “Mexican” to promote the upcoming “Mexico Week.” The accompanying dialog of the advertisement features the hosts “joking” that they probably should not make “Mexican jokes” because people might get upset. They even wrote the tweet as, “The juan [sic] and only Matt & Noel welcome you to Mexico Week!”

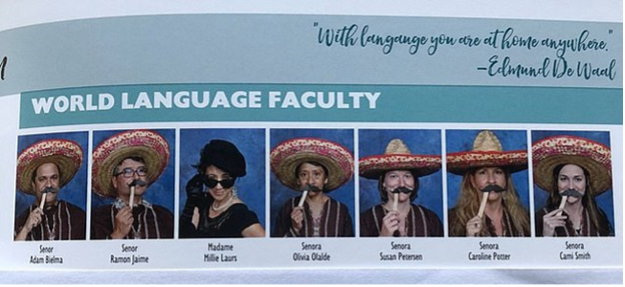

Another search result shows a group of foreign language teachers at San Pasqual High School in Escondido, California, who dressed up for their yearbook photos by wearing costumes based on the language they taught.

Of the seven teachers, six donned sombreros, serapes, and even large mustaches (the seventh, a French teacher, wore a beret). After a student complaint, the school released a statement that the photos were “culturally insensitive and in poor judgment.” While one Latino parent did not see the harm saying, “They could be offensive if they’re making fun of us [but] it could be something honorable if they’re trying to honor the Mexican culture,” the principal retorted, “Cultural appropriation is offensive, even if the intent is not to offend.”

Not everyone sees the harm. To be clear, in my daughter’s class, a clear majority of parents purchased the shirt.

Yet, there is a long history in the United States of stereotyping and homogenizing all people of Spanish-speaking descent as being merely backward, exploitable, and ignorant peon, migrant farmworkers from Mexico. Herein lies the harm in cultural appropriation.

The first issue, that of using a sombrero to denote all Latinx culture, is both problematic and the most straightforward.

Spanish immersion programs and Spanish language acquisition (like that in my daughter’s school and at San Pasqual High School ) teach appreciation for all Spanish-speaking countries. Using iconography associated with Mexico negates the rich cultural tapestries that exist among Spanish-speaking countries.

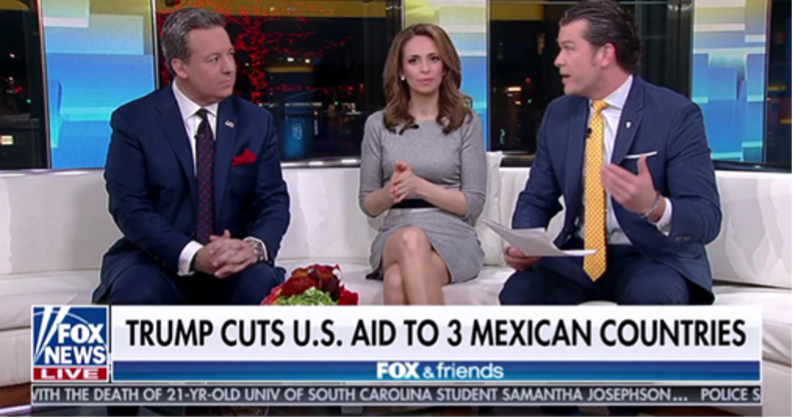

Unfortunately a common trope among U.S. Anglos is to view all Spanish speakers as “Mexican.” This was clearly seen in the now infamous 2019 Fox News Network Banner that read “Trump Cuts U.S. Aid to 3 Mexican Countries” while discussing Donald Trump’s decision to cut foreign aid to El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras until they helped reduce the flow of migrants headed to the U.S. border.

This mislabeling illustrates what people of Latinx descent experience in everyday life—the assumption of being both foreign and of Mexican descent, no matter their citizenship status or cultural lineage.

A deeper and darker history in the U.S. can be seen in how clothing became a specific symbol that embodied Mexicanness to Anglo minds and resulted in caricaturing.

For example, during the Bracero Program (1942-64) the sombrero became associated with Mexican farmworkers, not merely as an article of clothing that protected them from the heat but as part of a compulsory and costumed act potential braceros wore when seeking employment. It became part of their transformation into being viewed as single function commodities that the U.S. Agribusiness imported, exploited, and then discarded at the end of their contracts.

As historian Deborah Cohen illustrates in Braceros: Migrant Citizens and Transnational Subjects in the Postwar United States and Mexico, prospective braceros had to attend “casting calls” to join the international labor program. Anglo agents were looking for what they stereotyped as their ideal farmworker: dark skin, calloused hands, and peasant attire, especially huaraches and straw sombreros.

They did not want city slickers who they thought might faint in the fields. The agents sought what they considered the Mexican farmworker, complete with a sombrero on his head or humbly in his hand, reduced to their commodified body with only their labor to sell.

Cohen explains, Braceros had the “need to perform a backwardness that conflated Mexicanness with the rural, the uneducated, the peasant, the Indian.” This negatively stigmatized Mexican Braceros and all Mexican Americans by extension. Their clothing—homemade sombreros and serapes—made them appear poor, foreign, and exotic to Anglo America.

Thus, their appearance reduced people of Mexican descent to the Other, to inferior outsiders. “Mexican” became a race that personified qualities such as the type of work performed, as a lower standard of living, as poor health and hygiene, and as carriers of disease.

Much of this constructed imagery was based on their clothing specifically.

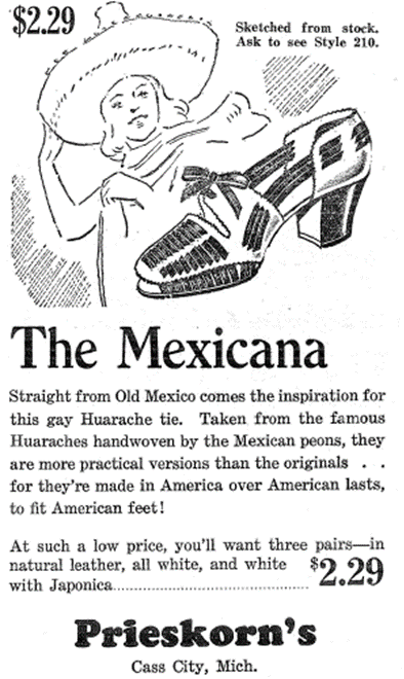

Take a 1939 newspaper advertisement in the Cass City Chronicle (Michigan). It features a sketched image of a Mexicana in a straw sombrero with a shoe in the foreground. The text under the image states, “Straight from Old Mexico comes the inspiration for this gay Huarache tie. Taken from the famous Huaraches handwoven by the Mexican peons, they are more practical versions than the originals for they’re made in America over American lasts, to fit American feet!”

Notice the connection between substandard Mexico-produced goods and the “peon” Mexican laborer, depicted with sombrero.

This racist rhetoric also goes back to the 1920s immigration debates when legislators attempted to add Mexico to the quota system.

The legislative testimony was quite dehumanizing, reducing farmworkers—typecasting all people of Mexican descent in the process—into second-class status. A government report on Mexican immigration during the 1920s reads, “The most ignorant, most oppressed, and poorest people of that country, composing its peon class, are furnishing almost the entire volume of Mexican immigration…Nearly all of them [are] engaged in common, unskilled labor…”

The report continues, “Many of these laborers are direct from Mexico and are…often shipped north still clad in the sombreros, light cotton clothing, and even sandals of the Mexican peon.”

Again, there is an inseparable connection between being Mexican, being poor peon laborers, and having inferior status, all visualized in clothing.

Supporters of the restrictionist bills went on to promote Mexican immigrants as dangerous to public health, decrying, “Mexicans are carriers of lice, bed bugs, and venereal diseases. They help spread disease” with another noting “children running around half clothed.” Their low economic status, their employment, their clothing, and their poor health was all intrinsically linked as somehow inherent to the so-called Mexican race.

Even those who were proponents of Mexican immigration, likewise, typecasted and demeaned those they referred to as “the Mexican.”

Representative Claude B. Hudspeth (D, TX) painted a definitive picture of this view. During the 1928 immigration debate, he stated, “The Mexican is a hot-house plant….He was born in a tropical country. He comes into this country with his little burro and cart and his wife and three or four children, poor, with very few clothes that is to do seasonable labor.”

No matter their view on immigration, the connection was clear. People of Mexican descent—and by extension anyone from Spanish speaking areas since most Anglos made no citizenship distinction—were viewed as exploitable and expendable first-class laborers but second-class humans/citizens.

Whether this mantra was predicated on economic exploitation, was a denigration assigned due to losing the Mexican American War, was a desire to maintain racial purity, or was to keep supposed dangerous and disease-ridden immigrants out of the country, the result was the same: This entrenched depiction of a certain type of Mexican immigrant—humble farmworkers dressed for field work—has left an indelible caricature that envisages a short, dark, weathered man wearing a sombrero on his head and serape over his shoulders.

As a result, with very few exceptions, when Anglos put on these garments in the 21st century, it is cultural appropriation at best, reinforcing a racist trope at worst.

Brett Olmsted has a Ph.D. in 20th century U.S. History with a focus on Latinx culture, labor, and immigration and is a Professor of History at San Jacinto College.

Art by Michelle Huang. Michelle read this piece and designed an original painting for Conceptions Review. Michelle is an artist from Sugar Land, Texas, now based out of New York, New York. She specializes in oil painting, known for her expressionist style in both figurative and abstract work. Her website is https://mhuangart.com.

Launched in March 2021, Conceptions Review is interested in the ideas people have about society and the consequences of these ideas. We seek accessible and standalone articles about conception-bending ideas and popular misconceptions. We are open to fields ranging from musicology to history to mathematics to insectology and everything in between.